How Freddie Mercury Stared Down Mortality on Queen’s ‘Innuendo’

Queen toiled away on their 14th studio album throughout 1989 and 1990, while fans eagerly awaited the end result — unaware that it would be the last to see release during frontman Freddie Mercury's lifetime.

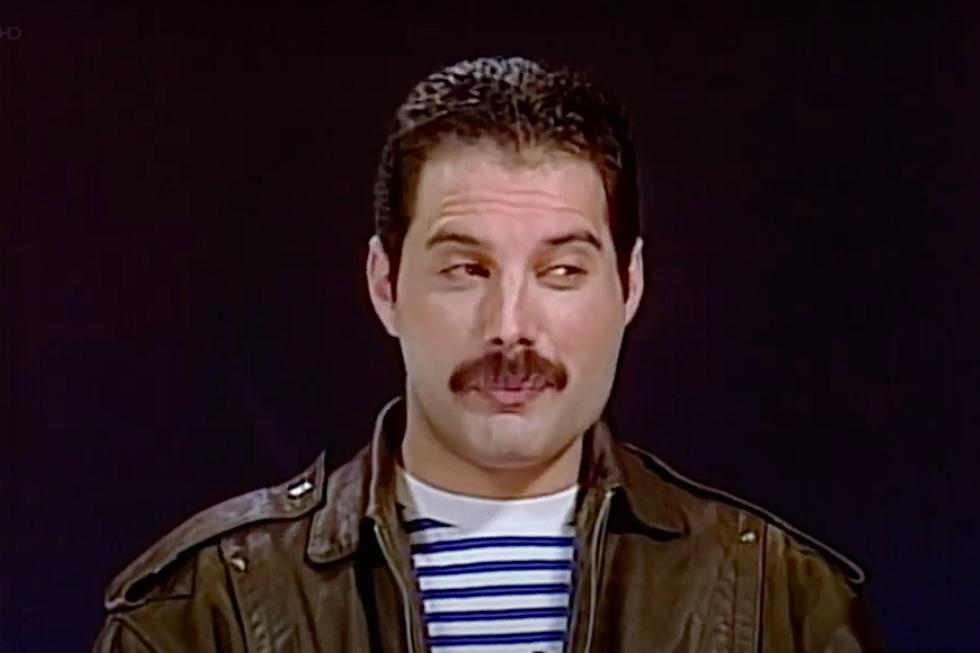

Mercury had been dogged by rumors regarding his allegedly ill health for years, and they'd only intensified after Queen decided not to tour in support of their most recent release, 1989's The Miracle. But the band had always brushed off those reports as tabloid fodder, and Mercury had always been a private performer who rarely interacted with the media anyway. As far as fans knew, the group's absence from the stage — and the delays leading up to the release of their next album — was nothing to worry about.

But behind the scenes, Mercury was fighting for his life. Diagnosed with AIDS in the spring of 1987, he'd grappled with his condition privately for years, and didn't initially share the news with his bandmates. As guitarist Brian May later shared, it wasn't until after The Miracle's release that they truly understood what was happening.

"Gradually, I suppose in the last year and a bit, it became obvious what the problem was, or at least, fairly obvious — we still didn't know for sure. He's a very private person," said May. "And then, eventually, just a few months before, he did sit down and talk to us about it, and from that point on it was openly talked about among us. But we still didn't mention a word to anyone, not even our families, which is very difficult. When your friends look you in the eye and say, 'What's wrong?' and you say, 'Nothing,' it's very hard. So it was a big strain. It did something awful to our brains."

In the middle of all this turmoil, the band members sought a modicum of peace by decamping to Mountain Studios in Montreux, where the secluded setting allowed them to work on new music without worrying about the paparazzi dogging Mercury. As they had with The Miracle, they opted to credit each composition to the band as a whole, helping to keep ego out of the track selection process. Although Mercury's declining health sapped him of his strength, he refused to scale back the vocal demands of the new material, digging deep to deliver some of his best work during the sessions.

There would be no tamping down the gossip surrounding Mercury's condition, especially after the band showed up to accept an honor at the Brit Awards on Feb. 18, 1990. The dynamic frontman, visibly gaunt, hung back while May spoke on the group's behalf, only leaning into the mic just before leaving the stage to say "thank you ... goodnight." It would prove to be his final public appearance.

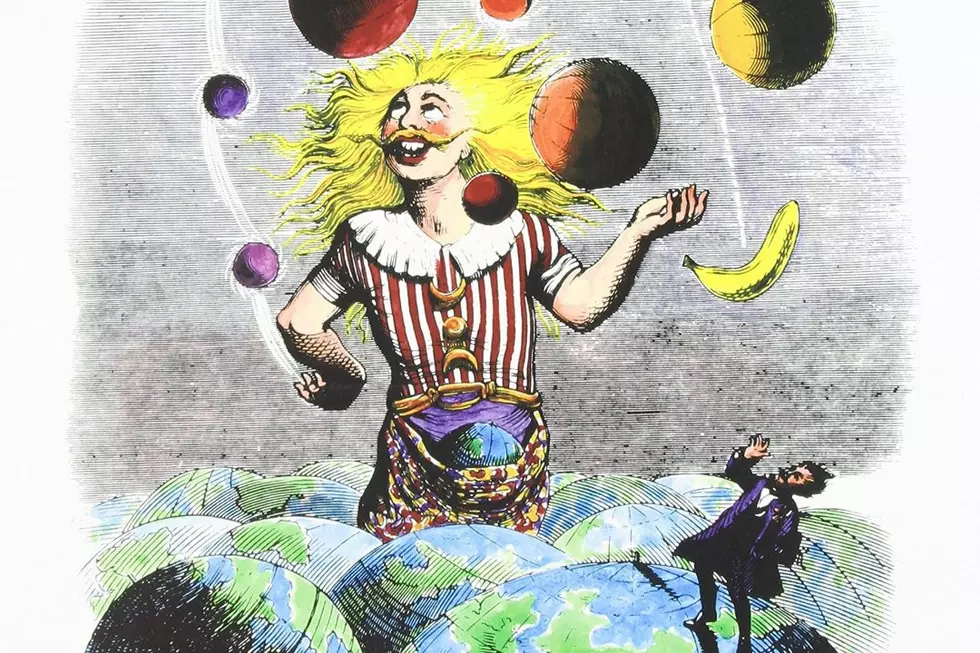

Perhaps fittingly, the group decided to call the new album Innuendo. Initially planned for release in the fourth quarter of 1990, it had to be held over until the next year, finally arriving on Feb. 5, 1991. With the title track, which also served as the lead-off single, Queen opened the album with a defiant tour de force — featuring guest guitar work from Yes veteran Steve Howe — that obliquely hinted at their behind-the-scenes drama while proving no one in the band had lost a step musically. In their native U.K., the single went to No. 1, while in the U.S., it cracked the Top 20 on Billboard's Mainstream Rock chart.

Watch Queen's 'Innuendo' Video

Overall reaction to the album was somewhat more muted. As they'd been for some of the group's more recent releases, reviews for Innuendo were largely lukewarm, and though it topped the charts in the U.K., it stalled at No. 30 in the U.S., achieving roughly the same chart peak as its predecessor while also going gold.

None of it weakened Mercury's resolve to keep his illness private — as he'd put it, "I don’t want people buying Queen music out of sympathy" — or kept him from cajoling his bandmates back into the studio so he could "keep working until I f---ing drop."

Those recordings would eventually reach the public with the release of the Made in Heaven album in 1995, but Mercury wouldn't live to see it happen. While filming the video for the Innuendo single "These Are the Days of Our Lives," he could no longer even feign at disguising his illness, and shortly after its release, he contacted Queen manager Jim Beach with his decision to go public. On Nov. 23, 1991, he released a statement informing the world of his diagnosis.

"Following the enormous conjecture in the press over the last two weeks, I wish to confirm that I have been tested HIV positive and have AIDS," wrote Mercury. "I felt it correct to keep this information private to date to protect the privacy of those around me. However, the time has come now for my friends and fans around the world to know the truth and I hope that everyone will join with my doctors and all those worldwide in the fight against this terrible disease. My privacy has always been very special to me and I am famous for my lack of interviews. Please understand this policy will continue."

One day later, he was gone. On Nov. 24, Mercury passed away at the age of 45, leaving behind a singular musical legacy and facing his mortality the same way he did everything else — on his terms.

Indeed, even though Mercury's death prompted a reappraisal of his work, as well as a public discussion of his lifestyle, more than anything else, he lived as an artist, and when he was faced with his own death, he did the only thing he could do: he created, and he kept right on doing it until he was no longer able. In that sense, although he was utterly unique, Mercury also made himself part of a broader tradition that includes a number of artists who used their art to greet — or combat — their mortality.

Unfortunately, as classic rockers age, this list only grows longer, and includes artists who redoubled their creative efforts while publicly fighting life-threatening illnesses — such as Black Sabbath's Tony Iommi and Def Leppard's Vivian Campbell — as well as those who use their last days to make a final statement, as Dan Fogelberg did with his posthumous Love in Time.

Final Albums: 41 of Rock's Most Memorable Farewells

Queen’s Outsized Influence

More From WPDH-WPDA