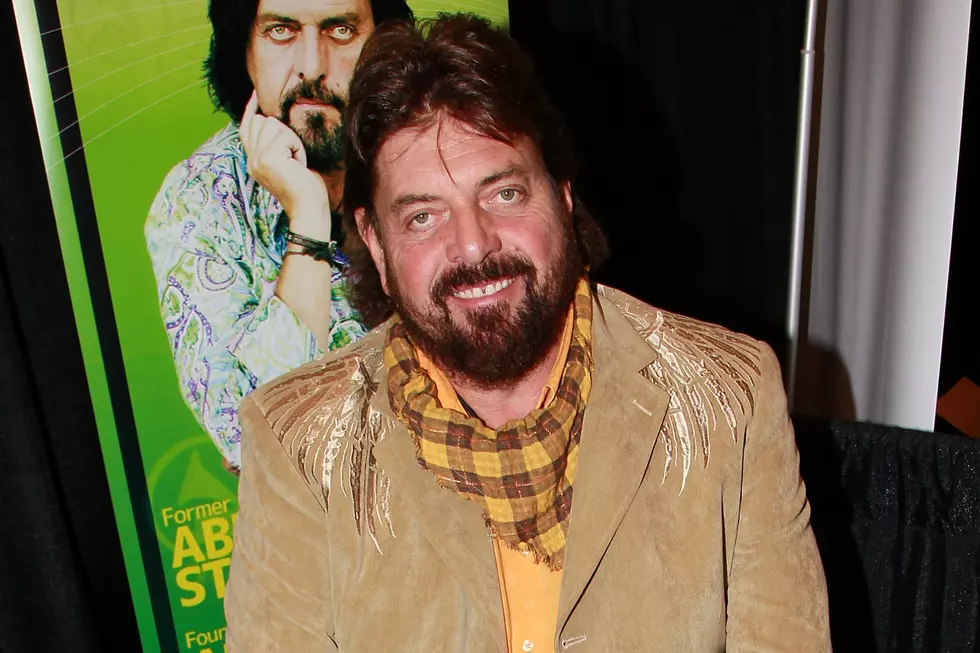

Why Alan Parsons Might Return to Pink Floyd’s Weirdest Album Idea: Exclusive Interview

Alan Parsons was already one of rock's most revered sonic craftsmen, long before establishing separate fame as namesake of the Alan Parsons Project.

He'd become an assistant engineer at the age of 18, earning an early credit on the Beatles' Abbey Road. He later served as an engineer for the first two albums from Paul McCartney and Wings, five studio projects by the Hollies and – most notably – Pink Floyd's The Dark Side of the Moon, which earned Parsons the first of many Grammy nominations. He also made key contributions to the careers of Al Stewart ("Year of the Cat"), Ambrosia ("Holdin' on to Yesterday") and Pilot ("Magic"), among others.

Parsons declined to take part in Pink Floyd's Wish You Were Here, the follow-up to The Dark Side of the Moon, in order to launch his own band. He and chief collaborator Eric Woolfson initially built the Alan Parsons Project around members of Pilot, though the lineups later began to regularly shift. They scored seven Top 40 hit songs and two platinum-selling Billboard Top 10 albums before splitting in 1990. Woolfson died in 2009 following a battle with kidney cancer.

By then, Parsons had already begun a sporadic solo career. He later launched the Alan Parsons Live Project as a way to present his group's songs on stage to a new generation. Now, he's back in the studio. The Secret, Parsons' first album in 15 years, follows A Valid Path – which saw Parsons reunite with David Gilmour of Pink Floyd and David Pack of Ambrosia. Guests this time around include Steve Hackett and Lou Gramm.

In an exclusive interview with UCR, Alan Parsons discusses how he crafted a loose theme for The Secret, as well as memorable career intersections with Pink Floyd and the Beatles.

The Secret seems to explore the multiple meanings of the word "magic" and the various ways it manifests in the world.

Magic is a passion of childhood for me. I've enjoyed performing magic in my own little way with friends and families – just card tricks and stuff in bars. I have a lot of friends who are magicians. I'm a member of the famous Magic Castle [nightclub] in Hollywood. We go there as often as we can.

It sounds like a fascinating place.

It's a wonderful place. There are a lot of little rooms where you can go in and watch magic at various levels of intimacy. There's a bigger theater where they do grand illusions, and there are wonderful little theaters with close-up magic. It's amazing. It has a great restaurant and several bars where magicians circulate and do tricks.

Watch Alan Parson's 'I Can't Get There From Here' Video

As a magician yourself, what's your level of expertise?

I've never had a paid gig, so it can't be that much. [Laughs.] I just do it for fun. I have an enormous number of magic books, which tend to just gather dust, waiting to be opened. I would spend every second of every day with magic if I could, but life gets in the way.

Since you gathered material from a lot of different writers, how were you able to focus this album on one theme?

I knew that the album would be based on magic at the beginning before anything was written. That was always the intention, and that was the brief to the musicians: "Any songs you write, make sure there's a reference in there." I think we succeeded on most of them. It's hard to find a magic theme in "Sometimes," the song Lou Gramm sings. But I think all the others have some kind of magic reference in there.

Speaking of thematic concepts, you've expressed frustration over the years that Pink Floyd never completed their aborted Household Objects project. That's still such a beautiful idea: creating landscapes from everyday sounds created by things like rubber bands and wine glasses. Were you immediately on board with that when they first came up with it?

I thought it was a brilliant idea, and I also proposed that not only would it be recorded without any conventional musical instruments but that it would all be recorded on one microphone – obviously with several layers of overdubs. I kept one microphone in a field box ready to be taken out with anything needed to be recorded. The problem with the project is that it seemed to be taking so long to get anything recorded. We'd put up the rubber bands and get a bass line going, and that was a whole day's work. And then drums have to be added to that. The wine glasses were good because they eventually reached a final destination [at the beginning of "Shine on You Crazy Diamond"] on a Pink Floyd album. But we were just going nuts: "This is gonna take years of painstaking recording time." They just abandoned it and said, "We can't go through this," which is a shame.

It was definitely a novel idea.

I think I could go for one song done that way but not a whole album. [Laughs.] I'll think about doing that at some point in the future.

Watch Alan Parsons Project Perform 'One Note Symphony'

It's funny, the 2019 On the Blue Cruise was almost like "Six Degrees of Alan Parsons" with David Pack of Ambrosia, Al Stewart, even the Pink Floyd tribute band.

And Steve Hackett was a recent connection.

Exactly. Was it a sort of reunion for you?

Let me put it another way: I wasn't left alone for very long. Al had a great little wine-tasting event with a few songs. He's a huge wine aficionado. He managed to spot a bottle of Cabernet Sauvignon [filled] with not-Cabernet-Sauvignon. He read the small print on the bottle, and sure enough it had some Cabernet Franc in it. [Laughs.] He really has incredible taste in wine.

I've always been a huge fan of the first couple Ambrosia albums, which you were involved with, and I feel like we're long overdue for a reissue campaign of that early stuff. Has anyone approached you about that kind of project? Would you be interested?

Yeah, I just spoke to David [recently], and he's full of the joy of having got three of the albums back from the label. So, that might mean a re-release at least. Not sure about a remix. I'd gladly remix it in surround form. I love mixing in surround. Sadly, the albums I did they did not get back, so I don't know what the status is of those. Hopefully, we'll get those back eventually.

When I first heard of the magic theme on The Secret, one of the first things I thought about was "Magic Alex," the infamous Beatles associate who cost the band a fortune with his ill-fated recording-studio experiments. You, of course, saw a lot of that first-hand. Magic is sometimes in the eye of the beholder.

My only memory really is Glyn Johns sitting at the console, shaking his head in disbelief. He said, "I can't work with this." They sent for some consoles to be sent down from Abbey Road, and that's what saved the sessions – the fact that Abbey Road had two mobile consoles laying around that they were able to install. On the last day, we ran those cables up to the rooftop and did the rooftop sessions.

Somehow I didn't realize until recently that photographic evidence exists of you being on the rooftop during the performance.

There are two known shots of me on the roof. But If I wanted to be a film star, I put myself in the wrong place: I was right behind one of the cameras. One place you're not going to become a movie star is if you're behind the camera, not in front of it.

Rock’s Most Underrated Albums

More From WPDH-WPDA